(An abridged version of this article previously appeared in the 1999 PBP Yearbook published by Randonneurs USA.)

A SHORT HISTORY OF PARIS-BREST-PARIS

©Bill Bryant 1999, 2003, 2021, 2026

First run in 1891, the 1,200-kilometer Paris-Brest-Paris is a grueling test of human endurance and cycling ability. “PBP”, as it is commonly called, is organized every four years by the Audax Club Parisien and its Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneur is the oldest bicycling event still run on a regular basis on the open road. (An Australian track race and a British hill climb, started in 1887 and 1886, respectively, continue into modern times.) Beginning on the southwestern side of the French capital in the town of Rambouillet, PBP travels west to the port city of Brest on the Atlantic Ocean and back. Today’s participants, while no longer riding the primitive machines used 135 years ago on dirt roads and cobblestones, must still face up to rough weather, endless hills, and pedaling around the clock. A 90-hour time limit ensures that only the hardiest randonneurs and randonneuses earn the prestigious PBP finisher’s medal and have their name entered into the event’s Great Book along with every other finisher going back to the first edition. To become a PBP ancien (or ancienne for women) is to join an elite fraternity of cyclists who have successfully completed this mighty challenge. No longer a contest for professional racing cyclists (whose entry is now forbidden), PBP evolved into a timed randonnée or brevet for hard-riding amateurs during the middle part of the 20th century.

The Racing Years

In 1891 people didn’t know what could be done on the bicycle. Some medical experts of the day decried its alleged harm to the human body, while more than a few members of the clergy said the same about the potential damage to the rider’s soul from riding on Sundays. Some women boldly insisted on riding bikes, just like men! Racing on velodromes in front of throngs of spectators had begun ten years earlier and cycling around town by wealthy enthusiasts was common enough, but the idea of covering long distances on the open road was still in its infancy. Nonetheless, as the turn of the century approached, ideas about what this fascinating new invention could do began to expand.

Early attempts at road racing and touring over hill and dale had started some years earlier but were still uncommon. Rutted and dusty in dry weather or muddy after rain, the unpaved roads of the time were frequently in poor condition. Encountered mostly in cities, bumpy cobblestones were often destructive to the fragile bicycle wheels as well. Despite that, the inaugural Bordeaux-to-Paris was held in the spring of 1891, a race on the open road that covered a whopping 572 kilometers. It took the winner, G.P. Mills of England, only 27 hours to arrive in Paris. The sheer audacity of the event captured the public’s attention and newspaper sales shot up for days before and after. This wasn’t lost on the editor (and devoted cycling enthusiast) of Le Petit Journal, Pierre Giffard. Also not lost was the fact that foreign riders had dominated Bordeaux-Paris from start to finish—the first Frenchman was a distant fifth place.

The inaugural Paris-Brest-Paris was announced for early September of 1891. Giffard intended it to be the supreme test of bicycle reliability and the willpower of its rider. He didn’t miss the mark: at 1,200 kilometers, PBP would make Bordeaux-Paris seem like child’s play. Only male French cyclists were allowed to enter. Each rider could have up to ten paid pacers strategically placed along the route to help with drafting and providing mechanical assistance. (Though a common racing practice of the time, only a handful of the most well-sponsored racers employed pacers at PBP.) Since reliable automobiles were still some years off into the future, the race would be monitored by a system of event judges and observers connected along the route by train and telegraph. Newspaper reporters would, of course, send their dispatches back to Paris so that the public could be supplied with special editions reporting the race as it occurred. PBP also caught the attention of bicycle and tire manufacturers wanting to show the cycling-crazy public that their products were superior to other brands, especially firms with the new pneumatic tires that rolled much better than the older wheels with solid rubber tires. Along with it being a race, the first PBP was also intended to show the reliability of bicycles. Normal repairs could be made, but the same frame, fork, and hubs had to be used from start to finish. These parts of the cycle were affixed with special seals, which had to remain intact throughout the event. Any missing seals meant disqualification of the rider.

Unlike the modern rural PBP route which avoids the busier highways west of Paris, the original route followed the Great West Road to Brest, or Route Nationale 12 as it came to be known, through the cities of La Queue-en-Yveline, Mortagne-au-Perche, Pré-en-Pail, Laval, Montauban-de-Bretagne, Saint Brieuc, and Morlaix. Riders were required to stop in each of these contrôle towns and have their route book signed and stamped at each checkpoint, a practice still done today. Event officials also inspected their machine to see if all the seals were still intact. No one knew how long it would take to cycle the extraordinary distance, and nay-sayers were convinced it couldn’t be done at all; some even claimed that the foolish riders might die in the attempt! During that summer of 1891, in a simpler place and time than ours, French newspapers were filled with stories and speculation about the upcoming test and the public’s imagination was riveted on this outstanding wager of audacity and determination. Over 400 riders entered the inaugural PBP, but many apparently came to their senses; 206 brave cyclists, all wearing their colorful PBP armband, eventually set off just before sunrise on September 6th amid great pomp and ceremony. How many, everyone in the vast crowds wondered, would make it back to Paris in one piece?

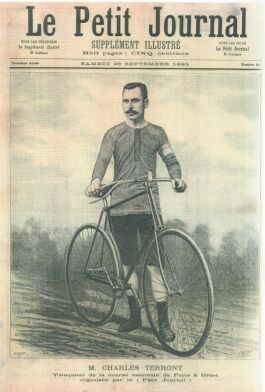

Alerted by newspaper reports, fans turned out along the route. The race soon turned into a contest between two men, Charles Terront and Jiel-Laval. Hundreds of race fans in Brest were astonished to see Jiel-Laval arrive after only 33 hours, with Terront about an hour behind due to some punctures. At that time, the fastest horseback rider, changing horses along the way, needed 54 hours for the same trip! Widely reported in the press and discussed by the public, the first edition of PBP was a huge success. The winner, Charles Terront, triumphantly, albeit wearily, pedaled into Paris at dawn three days later. He had been on the road for slightly less than 72 sleepless hours. Despite the early hour, over ten thousand cheering spectators were awaiting his arrival. His was an epic ride against his competitors and nature itself, and Terront became national celebrity. A little over half the starters gave up along the way and got themselves to the nearest train station, while one hundred survivors continued to trickle into Paris over the next seven days. Along with prize money to 17th place, these lion-hearted heroes were all given a handsome commemorative medal inscribed with their name and time. The legend of Paris-Brest-Paris was born.

After the first event in 1891, there were PBP races in 1901, 1911, 1921, 1931, 1948, and 1951. The ten-year interval seemed to reflect the difficulty of organizing such a long race, and because the Herculean event was so hard on the racers themselves—one PBP in a rider’s career was widely felt to be more than enough! Though the starting fields at each PBP professional race were small with 25-45 riders, most editions, especially the earliest ones, attracted the best endurance racers of the day. For example, already twice victorious in Paris-Roubaix, the winner of the 1901 PBP race was Maurice Garin, who would then go on to win the inaugural Tour de France in 1903.

The second PBP was also significant because entry was opened to foreign racers and this made it a legitimate sporting contest. Among the starters in 1901 was Chicago’s Charly Miller, a successful long-distance track event specialist. Under-funded for PBP, Miller lacked most of the team support his rivals employed, particularly the all-important pacers. Nonetheless, Miller would doggedly persevere alone through bad luck with numerous punctures and a broken bicycle. He arrived back in Paris on a hastily borrowed replacement for a fine fifth-place finish and widespread acclaim. His fast time of 56 hours, 40 minutes is still a remarkable feat that most modern riders would love to achieve. Thus, the 26-year-old Miller was the first American to enter, and complete PBP. Moreover, Charly Miller’s self-reliance and stubborn determination remain an excellent model for today’s randonneurs and randonneuses to emulate.

Beginning in 1901, the PBP entrants were divided into two groups: the fast coureurs de vitesse and the slower touristes-routiers. These hardy amateurs, denied all the team support given to the racers, were the predecessors of today’s self-sufficient randonneurs. They often numbered over a hundred in each PBP until 1931. Another big change came in 1911; no pacers were allowed to help the racers, as had been the practice in the first two PBPs. Now the contenders would have to make do with teammates who rode every inch of the course alongside their team leader.

In 1931 another fundamental change came to PBP. While still a prestigious professional race, the organizers dropped the category for the unglamorous touristes-routiers. Luckily for today’s randonneurs, the Audax Club Parisien (ACP) stepped in and organized a 1,200-kilometer brevet run alongside the race. Entrance was predicated upon having done a successful 300-kilometer brevet. (Tandem stokers could get in with just a 200-kilometer brevet to their credit.) Sixty randonneurs took the route that year, among them several women, a PBP first. A few randonneuses were on tandems and two used solo bikes. Riding with her husband Jean on a tandem, Madame Germaine Danis clocked in at 88 hours and became the first woman to finish PBP. Mademoiselle Paulette Vassard came in five hours later to become PBP’s first female solo rider. (In those days the ACP set the time limit at 96 hours; it would switch, reflecting better the roads and bicycles of the post-World War II era, to the current limit of 90 hours in 1966.)

(The ACP’s arch-rival club, the Union des Audax Parisiens, didn’t want to be upstaged and put on a similar event one day after the randonneur PBP for its “always riding as a group” members, but they didn’t allow any women or tandems in their PBP at that time. Very much believing in the camaraderie of “all for one, one for all” in their strictly scheduled version of PBP, the big audax peloton intentionally arrives back in Paris together after 85 hours on the road. Thus, it never truly resembled the faster free-paced randonneur version, which is somewhat closer to the unpredictability of a road race, at least among the front riders. The Union des Audax Française, successor to the UAP, has continued to organize the PBP Audax at five-year intervals since 1951. For many years it had more participants than the randonneur version, but since the 1980s the free-pace version has grown tremendously while the audax event has dwindled to alarming proportions and its future seems in doubt. Hopefully it can be resuscitated in the future.)

Changes among touristes-routiers and randonneurs aside, 1931 was an epic PBP race, arguably the best of all. Run in wretched weather, it was fought tooth and nail by men of iron. After various breakaway attempts, chases, and counterattacks, the race ended in a desperate sprint among five exhausted racers on the banked boards of the Buffalo Velodrome in Paris. The worthy winner was the great Australian endurance racer Hubert Opperman, or “Oppy” as he was popularly known. Riding solo and outnumbered by rivals with supporting teammates, his cycling prowess and never-say-die Aussie toughness thrilled race fans and made him a hero in France and at home.

Not surprisingly, there wasn’t a PBP event held in 1941 due to World War II. The sport of cycling was largely on hold across Europe, with a few exceptions here and there such as hollow versions of the one-day Tour of Flanders or Paris-Roubaix races. (Despite a distinct lack of well-trained, high-caliber racing cyclists and proper equipment, some ersatz bicycle races were run as morale boosters to remind those nations vanquished by the Nazis that life was getting back to normal in 1941-44. It didn’t work; real cycle racing only resumed after Germany’s defeat.) There was some effort given to organizing a PBP race for 1941, but the inevitable night riding would have violated the strict civilian curfew imposed by the harsh German occupation forces. In addition, Brest had become an important German naval base, and a bicycle race was not going to be allowed to go there, and so the idea was eventually dropped. Alas, in the following three years, Brest suffered immensely at the hands of the American air and land forces trying to capture the city. By September of 1944, eighty-five percent of Brest lay in total ruin, and its citizens faced a long period of reconstruction during the decades to follow.

A post-war PBP race was promoted in 1948 to take the place of the lost 1941 event, and the traditional system of using years ending in a “1” was resumed in 1951. As things turned out, that was the last time there was a professional race at PBP. Hard-fought from the start, it was a grand battle despite rain much of the time. However, there were also favorable winds for much of the race; the strong tailwinds from the start in Paris died down as the peloton reached Brest. Frenchman Maurice Diot arrived back in Paris after only 39 hours on the road. With a pack of chasers hot on their heels, Diot narrowly outsprinted breakaway companion Edouard Muller on the Parc des Princes Velodrome to take the victory—after gallantly waiting for Muller to get a wheel change following an unlucky puncture on the outskirts of Paris! Diot’s sterling example of sportsmanship was a fine way for the last racing version of PBP to end.

Attempts were made to organize PBP races in 1956 and again in 1961, but both events were cancelled for lack of interest among the racers. The long-distance training PBP required was in direct conflict with the lucrative month-long criterium season that followed each July’s Tour de France. Few, if any, riders wanted to dedicate themselves to preparing for the rigors of PBP and then gamble that they would win some prize money at the end of 1,200 grueling kilometers; they could earn much more by riding the short daily races in cities and villages around France throughout August. The guaranteed appearance money offered them was hard to ignore, plus they got to sleep each night. The PBP race promoters reluctantly gave up and turned over their event to the French cycle-touring federation and gave the event’s Great Book of Finishers to the Audax Club Parisien. An era had ended; after 1951 PBP was no longer une course professionelle.

The Randonneuring Years

As interest in PBP among the professional racing world died out in the years following World War II, the amateur versions—both randonneur and audax—would keep PBP very much alive. There have been ACP Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneurs events in 1931, 1948, 1951, 1956, 1961, 1966, 1971, 1975, 1979, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023.

Well-attended for the times, the immediate post-war Paris-Brest-Paris events saw much enthusiasm in a country trying to forget its wartime nightmares and privations. Along with the free-paced, freewheeling randonneur event, the controlled-pace audax version was also very popular, as was club cycling in general throughout France. In fact, the audax PBP often had more participants than the randonneur version into the 1980s. After 1951 the two clubs decided to schedule the event at five-year intervals. Interestingly, the three PBP randonnées of 1948, 1951, and 1956 saw men’s tandem teams outrun the solo bike riders and arrive back in Paris first.

If the days of the professionals were over at PBP, sometimes the ACP’s randonneur version didn’t look too different at the front of the “race” (aside from the compulsory use of fenders and the prohibition against any advertising on clothing). Each edition was hotly contested by dedicated amateurs, and they frequently turned in impressive performances. A few bicycle firms continued to support some of these fast randonneurs since sales of a particular brand would improve following a PBP “win”. There were many French successes but often with different riders. However, two names stand out time after time: Belgian Herman De Munck was at the front of affairs for many years beginning in 1966, while the American Scott Dickson dominated in a similar fashion from 1979 to 1999 without missing a single event. Clearly, Dickson and De Munck, like so many other hardy anciens and anciennes, truly love PBP despite its rigors. Perhaps 1931 winner Hubert Opperman described the difference between the two kinds of PBP cyclists best when he returned to Paris in 1971 to send off the randonneurs. Oppy told the riders, “I was a professional cyclist. I lived by the bicycle. You fellows are the real cyclists; you live for it.” These days, though, PBP as a race is clearly a sideshow to the PBP of modern times. It is now a timed brevet or randonnée where the vast majority of riders’ goal is to simply make it back to Paris inside the time limit and earn their finisher’s medal—not to defeat their fellow randonneurs and randonneuses. Camaraderie, not competition, is the main characteristic among most PBP entrants nowadays.

Following some very lean editions in the 1960s with less than 180 riders, the ACP’s PBP Randonneur grew tremendously under the energetic leadership of Bob and Suzanne Lepertel. The 1971 event had 325 starters, double that from 1966. Once entirely a domestic affair, by the 1970s increasing numbers of foreigners traveled to France to attempt PBP, especially riders from the United Kingdom and Belgium. More French randonneurs took up the challenge too. After 666 starters in 1975, 1,766 were at the next PBP in 1979. The 1980s showed strong growth, and by 1991 there were 2,860 participants for the big Centennial celebration. The continual growth at PBP brought some problems since organizing and supporting such an enormous event clearly over-burdened the ACP, a small bike club with less than 100 active members. The French cycle-touring federation has become more involved helping at PBP in recent years. In 2003 over 2,000 volunteers from regional bike clubs around western France helped put on the event; by 2019 the number of bénévoles working at the checkpoints had grown to 2,500.

After Charly Miller raced PBP in 1901, seventy long years would pass before the next cyclists from the United States attempted the ride, but neither Clifford Graves nor Ruby Curtis reached Brest in 1971. The second American to finish PBP successfully was Californian Creig Hoyt in 1975. Also finishing at intervals behind Hoyt were Herman Falsetti of Iowa, and randonneuses Catherine Anette Hillan, another Californian, and Harriet Fell of New York. The medals earned by this pioneering foursome in 1975 opened the door for future American randonneurs at PBP. Thirty-five of them rode PBP in 1979; by 1983 the number had risen to 107. The first Canadian randonneurs came to PBP in 1979. Four men from British Columbia entered and earned their medals: Wayne Phillips, John Hathaway, Gerry Pareja, and Dan McGuire. By 1999, 3573 participants from 24 nations took the start at PBP—including 398 Americans and 105 Canadians.

Along with the significant route change, the randonneur PBP took on much of its modern look with the 1979 event. After using roadside restaurants and hotels as checkpoints since 1891, the current practice of using large high school cafeterias was begun to handle the waves of hungry riders, with local cycling club volunteers staffing each control. A system of staggered starting groups was also initiated that year for similar reasons. There was yet another change in 1979; all entrants, foreign as well as French, now had to do a full Super Randonneur series of brevets (200-300-400-600 km) in the spring before PBP to enter. This requirement, more than any other factor, caused the growth of randonneuring beyond the borders of France. Randonneuring organizations started in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Spain, Belgium, and Australia in the early 1980s, then later in the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Brazil, and elsewhere.

With the steady increase of PBP participants in the 1970s one hallowed tradition had to give way to modernity: At some point the anciens’ names were no longer entered into the leather-bound ledger pages of the Great Book of Finishers. Now they are kept on computer-generated lists and available on-line. It would be ridiculous to think some ACP officer dutifully sits down to transcribe thousands of names and times by hand every four years. Nonetheless, many randonneurs still mention being “listed in the Great Book” as if it were in use today. It is a nice mental image not everyone is ready to discard, even if no longer true.

The PBP Centennial was celebrated in 1991 by the ACP and the UAF; both events were run simultaneously, and it was declared a grand success by all concerned. This was also the time when the two clubs decided to bury the hatchet, and relations have been cordial ever since. As a concession to the ever-growing congestion in the Paris region, the start location was moved to St. Quentin-en-Yvelines, a Parisian suburb near Versailles. Long gone are the days of a civilized mid-morning starting time for such a grueling ride. Due to justifiable safety concerns about launching thousands of randonneurs onto the busy roads around Paris, now Sunday afternoon and evening and 5 AM Monday morning starts are the norm. (Unfortunately, the evening starting times place an extra hardship on the slower participants, many of whom will suffer from worse sleep-deprivation later in the event.) In 1995, the ACP rules requiring fenders and prohibiting advertising on clothing were dropped, and some of the unique PBP atmosphere was lost.

PBP in the 21st Century

As the 20th century gave way to the 21st, the randonneur PBP continued its pattern of steady growth with more entrants from around the globe. During the 1980s, French randonneurs were about 75% of the field and foreign participants made up the rest. By 2019, those numbers had completely reversed, and the French riders totaled less than one-fourth of the participants. With riders from over 65 nations at the latest event, English is now the lingua Franca among the riders at PBP. (Most of the start/finish and checkpoint volunteers speak only French, however, and many foreign participants still struggle to communicate with them much of the time. Some checkpoints try to have a roving translator or two available when possible.)

In modern times the PBP route has remained fairly static after the big change in the 1979. On the return, Nogent-le-Roi was the penultimate control for many years, but in 2007 it was moved north to Dreux. (Most of the Nogent-le-Roi checkpoint volunteers came from the larger city of Dreux and so the route was changed to reflect that. And Dreux, like Mortagne-au-Perche, was on the original PBP route and this gave things a sense of historic symmetry.) A more noticeable route change came unexpectedly in 2019 after the city of St. Quentin-en-Yvelines abruptly decided to stop hosting PBP. The start/finish was moved some distance south to the old royal town of Rambouillet. Most participants liked this change because they were quickly onto pleasant cycling roads compared to the former start/finish location and its busy streets, but Rambouillet lacks enough lodgings and restaurants for such a large event. Many riders must use the train before and after the event, which adds another layer of complexity to participating in PBP. (At this writing, there are some notable route changes planned for 2027, but nothing that will fundamentally change the event.)

As always, there are still plenty of fast riders out to “do a time” at PBP but the ACP has gradually lessened the competitive aspects of their event since the turn of the century. They stopped publishing finishers by arrival time; now they are arranged alphabetically in country groupings. There is no longer a leading car showing the way for the fastest riders and they must follow the route arrows like everyone else. And there are no more trophies for the fastest male and female riders. (As before, there are still trophies for the clubs and countries with the most entrants, most finishers from one club, youngest finisher, oldest finisher, etc.) But as before, there are still plenty of fast riders who are trying to go as fast as they can.

A look at the numbers of participants in the most recent events shows the continuous growth at the randonneur PBP: 2003 had 4,069 starters; 2007 saw 5,160; there were 5,002 at 2011; 2015 had 5,870; 2019 saw 6,418 starters; and 2023 had 6,496. (All these events had larger numbers of entrants than the previous edition, but it is normal that there are a few hundred riders who decide to not take the start for various reasons, and this includes the 2011 variation.) Most of the events from 1987 forward had an approximate DNF (did not finish) rate of around 17-20%, somewhat higher than the notable 1979 and 1983 editions which saw DNF rates of only 10-11%.

The 2007 PBP stands out for having atrocious weather for most of the ride and many of the survivors arrived back in St. Quentin-en-Yvelines in a physical state that was alarming. It reminded veterans of the challenging weather at the 1987 PBP. The 2007 DNF rate shot up to about 30% but considering the abysmal weather conditions the riders endured, that seems rather low in retrospect. In a sport that celebrates determination and audacity, the 2007 PBP is legendary, and any finisher of that epic event is frequently shown extra respect by other randonneurs.

On the other hand, 2019 stands out as the modern PBP event with one of the worst completion rates ever, and this came as a surprise. That year 28% of the starters failed to finish inside their respective time limits. The weather was generally fair during the event but there was a steady headwind outbound to Brest (and sometimes on the return.) There were very cold nights throughout the event (but this has been true at other PBPs too.) Valuable lessons learned in previous events seemed to be ignored by too many of the 2019 riders, most of whom came unprepared with adequate clothing for the conditions. In older times it wasn’t uncommon to see larger saddlebags or handlebar bags in use at PBP and randonneurs usually carried several layers of warm clothing. But with today’s minimalist packing approach to make their bike lighter and more aerodynamic, too many of the randonneurs sacrificed having enough clothing. Or, as was observed by a number of PBP veterans, too many of the 2019 riders came physically and/or mentally unprepared for the event’s rigors. It was also theorized that some riders must have gotten into the event with unusually easy qualifying brevets and didn’t realize how difficult PBP could be. Whether too cold, or prematurely worn out, or lacking enough tenacity, a great many riders threw in the towel and became DNFs or arrived outside the time limit (OTL) for their starting group. The DNF/OTL rate among participants from many Asian countries was extraordinarily high. According to the event organizers, the overall DNF/OTL rate for Asia was 61.9%. The next worse was Africa at 33.3% and the Americas had a 31.3% rate. European riders tended to do much better and their collective success rate was along expected levels. The 2023 event got back to normal with an overall 21% DNF rate, despite some very hot daytime temperatures.

Still, despite so many DNFs, there were successes at the 2019 PBP. For most riders, it was simply being very determined and earning a finisher’s medal and getting their name entered in the Great Book. The oldest of them all was French randonneur Jean Guillot at age 86. French riders Jean-Claude Chabirand, Dominique Lamouller, and Alain Collongues astonished everyone by completing their 12th PBP Randonneur! Behind them seven riders have completed 11, and another seven riders have completed ten. Among women, Canadian Deirdre Arscott completed her ninth PBP in 2019, with French randonneuse Nicole Chabirand at eight. Five other randonneuses have seven PBP finishes apiece, including American Lois Springsteen. Among American randonneurs, Paul Bacho, Ken Billingsley, Thomas Gee, and Doug Kirby all earned their eighth PBP Randonneur medal that year.

In addition to individual successes, the event has improved in other ways. PBP began using electronic rider tracking at the most recent events. The traditional route book and control stamps are still used as a backup in case any of the vital rider data from a checkpoint is scrambled or lost (which has happened.) Even better, now friends and family back home can keep track of their randonneuse's or randonneur’s progress during the long ride via an on-line portal.

Also, the number of cheering spectators along the PBP route has grown and the riders’ morale is improved. They encounter many more supportive fans nowadays, and some of them are offering food and drink to help the cyclists on their long journey. These impromptu stops, along with finding more stores and cafés staying open beyond normal business hours, help them refuel in-between the crowded checkpoints. In addition, most controls now have a service rapide outdoor snack bar in addition to the familiar indoor cafeterias with tables, chairs, and a full menu of hot food choices. A number of other villages along the route are setting up organized stops selling food in-between the controls as well. Compared to earlier times, finding something to eat or drink during PBP is now much easier despite the larger number of entrants.

Finding places to get a few hours’ sleep are more numerous too (though the event could always use more.) In the region around Loudéac and Brest, the Audax Club Parisien developed more locations for sleep in recent editions. These simple rest spots might be nothing fancier than a wrestling mat or camping cot in a high school gymnasium or village meeting hall, but exhausted randonneurs aren’t going to complain. There are often waiting lines for food and sleep locations along the route, and these changes may not feel like an improvement. But compared to earlier editions of PBP—where there was nothing more than a village grocery store that closed at 6 PM or a crowded café to get some food before midnight, and perhaps sleeping rough along the roadside, or on the floor of a room filled with straw—recent PBPs have offered much more rider support than there was in the past, and most lines are shorter nowadays.

After the turn of the century the ACP revamped the mass starts of the 80-hour, 84-hour, and 90-hour groups and they began sending off numerous, smaller starting waves containing 250-300 riders. This has made several improvements. It ended some truly enormous rider packs’ impact on other road users; it lessened the crowding and long lines at the early controls; and it eliminated the shoving and crowding by fast riders trying to get to the front of their respective groups before the starting gun went off. The new system of riders choosing their own starting wave introduced in 2015 has probably been the best change of all—no longer did riders have to wait for hours to line up under a hot sun or in cold rain and then leave in one gigantic group; now they could show up just 20 minutes before their wave’s departure and be on their way.

The modern PBP has developed another problem to worry about, namely its popularity. By the time the planning began for the 2011 event it was clear the continual growth of PBP had to be curtailed. Along with the ever-increasing workload on the ACP and other volunteers, some civic authorities in western France were beginning to balk at issuing road-use permits for the huge event; they worried the extra traffic in various towns and cities along the route had become too-great a problem. More than the cyclists themselves, it was the vast armada of rental cars, camper-vans, RVs, and other vehicles used by many participants for personal support that were clogging the roads and parking areas. (PBP regulations require that riders’ support cars follow a designated route that is not on the cyclists’ route. Most of the problems come in the control towns where the two routes converge.) In response, the ACP instituted a new entry system of “pre-registration” that discouraged cyclists not serious about riding the event, but this also effectively meant two years of required randonneuring for all entrants instead of one. On the plus side, there is a tangible benefit to the new two-year system of entry registration; the longer one’s event in the year before PBP, the more choice one has for selecting their starting wave. (1000 km/1200 km brevet finishers get first choice; 600 km finishers get second choice; 400 km is third; and so on. Thus far, riders without any brevets in the year before PBP have gotten in successfully, but often in the least desirable starting waves.) The 2023 riders encountered a new rule that broke with past events: the intermediate checkpoint closing times would no longer be enforced, only the last one at the finish. This had been going on informally for several editions to varying degrees, and it was confusing, but now it was made official. PBP also had a new rule that required all participants to wear a helmet while cycling, and they could not wear the jersey from a professional cycling team. (As always, it was recommended that they wear the jersey from their cycling club or nation, or one that is plain.) 2023 also brought the requirement of wearing a helmet while riding. At any rate, three of the riders at the 2023 event had certainly witnessed a lot of the changes at PBP over recent decades—Frenchman Jean-Claude Chabirand completed his 13th Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneur, Canadian randonneuse Deirdre Arscott completed her tenth, and American Ken Billingsley earned his ninth PBP medal.

Looking forward, managing the continued popularity of PBP is likely the biggest challenge facing the event. Along with the small size of the organizing club and its aging membership, having thousands of sleep-deprived bicyclists on the open road is not something local authorities look forward to. (Hospital admissions in cities along the route see an increase during PBP, as does the workload for law enforcement personnel.) Obtaining road-use permits will remain a concern, as will dealing with so many private support vehicles clogging the streets of villages and towns along the way. As finally happened in 2019, it is likely future events will see a firm cap placed on the number of its participants. And given the crowds of riders at the checkpoints, this is probably a good thing—at least for those able to get entered successfully. That PBP is held only every four years makes the wait terribly painful for those inevitable riders who will be “hoping to do it next time.”

In August of 2027 the Audax Club Parisien will put on its 21st edition of the Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneur. Add those to the seven racing PBP events and one has a glorious history of determined cyclists daring themselves to get from Paris to Brest and back as quickly as their abilities will allow. To be sure, there have been many changes at PBP over the years but that shouldn’t be too surprising—our modern world has also changed a lot since 1891. Nonetheless, the challenges that confront today’s randonneurs at PBP remain timeless, hence its world-wide appeal and legendary status. What this short space doesn’t allow are the countless stories of bravery, heartbreak, struggle, and triumph that have come from the randonneurs and racers at Paris-Brest-Paris. This rich tapestry of human endeavor is what gives PBP its enduring mystique. Make no mistake: every PBP is a grueling test of endurance and not for the timid or unprepared. But the heroic virtues commonly found among the participants, both past and present, are eloquent testimony to the unconquerable human spirit. Vive le Paris-Brest-Paris Randonneur!

Sources: Résultats Plaquettes published by the Audax Club Parisien following the 1975, 1979, 1983, 1987, 1991, 1995, 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023 PBP events; Audax Club Parisien Newsletter, Jan-Feb 1914; Audax Club Parisien Newsletter, Sept-Oct 1951; Audax Club Parisien Newsletter, Oct-Nov-Dec 1961; Audax Club Parisien, Fête Ses 75 Ans 1904-1979; the Journal of the International Randonneurs, 1989 and 1990 editions; Coups de Pedals, Hors Série No. 2 (history of PBP races), Belgium, 1991; History of PBP: Racing and Touring by Robert Lepertel, Audax Club Parisien, 1986; A Brief History of the ACP by Robert Lepertel, Audax Club Parisien, 1996; Audax-UK Handbook, Year 2000; Paris-Brest et Retour by Bernard Déon, 1997; Old Roads and New by J. B. Wadley, 1971; 14e Paris-Brest-Paris: L’Epopée Fantastique, Cyclo-Passion magazine, October, 1999; Charles Terront & Paris-Brest-Paris by Andrew Ritchie, On The Wheel magazine, issues #10-12, 1999; La Saga du Tour de France by Serge Laget, 1990; Cyclotourisme magazine, Hors Série, No. 395 (1991 PBP special issue), France; Géants de la Route by Jean Durry; 1973.

©Bill Bryant 1999, 2003, 2021, 2026